A section on intelligence from Tony Cunnane's book "Tango Charlie Contact!" follows.

No 26 Signals Unit, at RAF Gatow and on top of Teufelsberg

I took this picture of Teufelsberg from the top of a nearby domestic radio transmitter.

After saying farewell to RAF North Luffenham, I went to the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in Cheltenham and the Ministry of Defence in London for further briefings. On 29 December 1977 I drove to Harwich and joined the overnight car ferry to Bremerhaven. After spending a comfortable night in a cabin, I drove south about 300 kms through Bremen and Hanover to Helmstedt, near Braunschweig. There I had to report in at the British Checkpoint Alpha where I was given a detailed briefing on the protocol for using the road corridor from the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland - BRD) across the German Democratic Republic (Deutsche Demokratische Republik - DDR aka East Germany) to West Berlin.

As someone who had spent much of his flying career in the V Bomber Force when the Soviet Union was treated as the main enemy, it seemed quite unreal, and vaguely alarming, that I was expected to drive myself unescorted through Soviet-controlled East Germany. It was a considerable relief when I reached the eastern end of the corridor without incident and booked in, first at the Soviet checkpoint at Dreilinden, and a few miles further on at Checkpoint Bravo at the southern end of the American Sector of West Berlin. (There is a more detailed account of the military road corridor protocols in a later page.)

For those not familiar with the Berlin situation in the late-1970s I should explain that from the end of World War II the city had been governed, not by the Germans, but by the four military powers: France, UK, USA and the Soviet Union. Each of the four Allied Powers had been allocated their own sector when the city was carved up. The American, the British, and the French Sectors were collectively known as West Berlin; the Soviet Sector was more usually referred to simply as East Berlin. The Germans were left out in the cold - which explains why the capital of West Germany was located in Bonn and not Berlin between 1949 and 1991. (Although after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 the government was not fully operational in Berlin's reconstructed Reichstag until 1999.) The city of Berlin, all four sectors, was entirely located inside East Germany. The Soviet Sector of Berlin, as well as being known as East Berlin, was the de facto capital of the DDR, although I believe only the East Germans and the Soviets officially acknowledged that.

Allied military and civilian air access to West Berlin was permitted only via one of three air corridors controlled by the Berlin Air Safety Centre (BASC) located in a splendid pre-war building in down-town West Berlin. BASC was a four-power organisation established soon after the end of the 1939-45 war. The air corridors were each 20 nautical miles wide fanning out from West Berlin and were still in force during my time in Berlin. The northern air corridor started at Tegel airfield in the French Sector for aircraft heading to and from the Hamburg area; the central air corridor, the shortest of the three, started at RAF Gatow in the British Sector for aircraft going to and from Hanover; the southern air corridor started at Tempelhof airport in the American Sector and ended near Frankfurt. Each of the four Allies took it in turn to be in command of BASC. Because of the nature of my work I was supposed to conceal the fact that I could speak Russian from anyone who did not need to know that. I and all personnel at 26SU were prohibited from visiting BASC and East Berlin.

The boundary between east and west was not always a wall - sometimes just a metal fence - in this case watched over from a very adjacent tower.

During the years of the Nazi regime, Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments and War Production for the Third Reich, had designed and built a military technical college in the western suburbs of Berlin on the banks of the Havel River in the lush Grunewald (Green Forest). After the end of the war the college was deliberately blown up by the Allies and the resultant rubble was piled up where the college had been. Over subsequent years another 25 million cubic metres of rubble from the rest of devastated Berlin were added to create the artificial hill which was eventually named Teufelsberg (Devil's Mountain).

On top of Teufelsberg was a US Army signals intelligence facility (the domes on the image at the top of this page) and the RAF's No 26 Signals Unit where I would be working for the next two and a half years. Within 26SU's accommodation at Teufelsberg there was a small UK Royal Signals Corps detachment; what they did was none of my concern and I will not mention them again.

As a reminder of RAF Gatow's importance during the Berlin Airlift in the late-1940s, the Station motto was 'pons heri, pons hodie': 'A bridge yesterday, a bridge today.' The airbase was located at the western edge of West Berlin right on the East German border. In fact, the western edge of the perimeter track around the airfield actually marked the border but there was no border crossing point there - the nearest was a few kilometres away at Staaken. Every night and day East German and Soviet border guards kept watch on Gatow airfield; the Air Traffic Control tower on the airfield also gave an excellent view across into East Germany.

I am taken to visit a number of locations that I should not have been taken to

Teufelsberg was just a short distance away from RAF Gatow as the crow flies, but the wide Havel River between the two meant that road traffic had to make a lengthy diversion via the Heerstrasse, a five kilometre, multi-lane highway running from the East German border at Staaken right into the centre of West Berlin. The Heerstrasse, which literally translates as Military Road, was always congested during daylight hours. I had to use it on my way to and from work, and every time I needed to visit the centre of Berlin on other duties or for pleasure.

The large building on the right was the SFB HQ (Sender Freies Berlin - Berlin radio and TV station).

There were road junctions every few hundred metres along the Heerstrasse, all controlled by traffic lights. I was fascinated, and irritated, by the traffic light control system - very advanced even by today's standards. Flashing digital light signals every 200 metres or so between junctions indicated the speed to drive at (between 20 and 50 kph) if you wished to connect with a green signal at the next junction. The system assumed that all drivers obeyed the maximum speed limit of 50 kph, very strictly enforced for all military vehicles but largely ignored by all others. Berliners were adept at working out how fast they needed to drive, anywhere between 60 and 90 kph, to reach an earlier green signal at the next junction. I suppose they could save several minutes on their daily commute when they got it right, but every now and again one of the drivers got it wrong, slammed on the brakes and caused vehicles behind to brake even more sharply hoping to avoid a nose-tail collision.

Incidentally, during my years in Germany there was a rule that was strictly enforced throughout the country as well as in West Berlin: any driver who collided with the vehicle in front was automatically deemed to be responsible for the collision, irrespective of what the driver in front had just done.

I started work at No 26 Signals Unit on New Year's Day 1978. Most of my first week was taken up with a series of operational briefings and visits to other intelligence organisations within West Berlin. On my first day I attended the standard 'Berlin Briefing' at RAF Gatow that all new arrivals had to go through and then my predecessor took me to Teufelsberg. Before I was allowed to enter the secure area I had to go through the security re-indoctrination process and only then was I issued with the pass which allowed me unhindered access to the secure areas. On the second day more briefings and then, in the evening, I went to the Philharmonic Hall to hear Elizabeth Schwarzkopf's final Berlin recital before her retirement. I can't now remember how I managed to get a ticket for that highly auspicious event that had, apparently, been over-subscribed for many weeks.

On the third day the Director of the US National Security Agency visited 26SU; he didn't come especially to see me, of course, but I sat in on his briefing and followed him around. I can't now remember his name but I believe he was new in the job.

On the 4th day my predecessor took me to visit BRIXMIS (The British Commanders'-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany) where I was given a detailed presentation of their role. I learned that BRIXMIS officers spent most of their time travelling around East Germany. The Soviets, Americans and French had their own versions of BRIXMIS. The idea, apparently, was that each of the four nations could keep track of what the others were doing and make sure they were not violating any military agreements.

On my fifth day I was ordered, at very short notice, to take the daily RAF flight to the Headquarters of RAF Germany, near Mönchengladbach, to meet the Command Intelligence Officer (CIO), a group captain by rank. He welcomed me and then gave me a warning. Someone had informed him that I had been to BRIXMIS the previous day. It was, he told me, strictly forbidden for personnel of BRIXMIS and 26SU to visit each other's establishments in Berlin, or to exchange intelligence data with them by any means. What the group captain appeared not to know, and I was not about to tell him, was that after visiting BRIXMIS my predecessor had also taken me to the US and French equivalent organisations in West Berlin.

The CIO accepted that I had been to BRIXMIS in all innocence; he said he would deal with my predecessor for having arranged it. The CIO told me that the reason for not allowing liaison between different field intelligence agencies was to prevent what was known in the trade as 'action on'. The assumption was that if two or more field agencies shared, or even discussed, any particular new intelligence and they then unilaterally acted upon it, it might reveal to the Soviets how the intelligence had been obtained. Revealing the source of your intelligence to your enemies was one of the greatest sins in the trade.

The CIO went on to explain that GCHQ always did the analysis of intelligence product in-house at Cheltenham because it was only GCHQ that had access to intelligence from all sources. GCHQ released intelligence to those who were known as 'the customers', defined as those on the front line who would actually make use of the intelligence to fight the Cold War. In the case of the RAF, he told me, Strike Command was the major customer.

When I got back to 26SU, relations between me and my predecessor were visibly strained: he didn't ask me what I had learned from the CIO - there had obviously been words exchanged between them but I have no idea what the outcome was.

Why there had initially been confusion about my appointment

Even in the suburbs, once wide streets were cut off by the Wall - often with a very obvious public viewing point..

I found that I had three titles at 26SU: I was Second in Command, Senior Intelligence Officer (SIO), and one of two senior subordinate commanders who between us were responsible for all matters concerning the discipline and careers of the junior officers, warrant officers, senior NCOs and airmen at 26SU.

The post of second in command was not one that the RAF generally used - not by that title anyway. For protocol reasons every independent unit in West Berlin, and there were dozens of them, was required to nominate a 2 i/c, presumably so that if the CO got bumped off suddenly, everyone would know who would immediately take his or her place! The British Military Government, which had its HQ in the Berlin Olympic Stadium, maintained the official list of all commanders and their deputies. Being 2 i/c of an independent military unit in West Berlin had both advantages and drawbacks, as I was to discover early in my tour of duty.

Most of the airmen who worked at Teufelsberg were either Russian, Polish or German linguists. The presence of the very tall red and white VHF/UHF radio mast on Teufelsberg gave a clue about how they were employed. Their trade was Radio Operator Voice (ROV) and they spent their entire career moving between the RAF's many signals units around the world gathering COMINT (communications intelligence). The airmen who worked in 4 Hangar on Gatow airfield were ROTs, Radio Operator Telegraphists; many of them had started their RAF careers as teleprinter operators but they were also trained in collecting other forms of data transmission known as ELINT (electronics intelligence). Before my tour at Teufelsberg was over, Elint was becoming more important than Comint and some ROT tasks were transferred from 4 Hangar to Teufelsberg.

There were two GCHQ civilians working at 26SU, one in No 4 Hangar on the airfield at Gatow and a more senior one at Teufelsberg. They were known officially as Technical Advisors and, unofficially by the airmen at 26SU, as 'the GCHQ spies'. The Technical Advisors were there to keep an eye on what the RAF staff were doing and to advise me, as SIO, on reporting procedures. The Senior Technical Advisor (STA) could, and did, communicate on a daily basis with his masters at GCHQ using a communication method to which I had no access. It was undoubtedly the STA's report to GCHQ of my visit to BRIXMIS that had resulted in my summons to Rheindahlen - all in the space of well under 24 hours.

Throughout my active service in the RAF there was no Intelligence Branch and, therefore, no dedicated intelligence officers; the reason for that dates back to the earliest years of the RAF's existence. One of Hugh Trenchard’s first decisions, when he was serving as the very first Chief of the Air Staff in 1918/19, had been that all RAF officers, with the exception of a few specialists like doctors, dentists and padres, were to be pilots. Officers would be commissioned into the what Trenchard called the General Duties Branch and be responsible for "carrying out the conduct and supervision of all aspects of flying and engineering, including armament, wireless and photography, and all staff and administrative duties". The GD Branch would also be responsible for providing the commanders of all operational units, which implied, of course, that only those officers would be eligible for promotion to the highest ranks of the new Service.

When I had been in Berlin for several months I learned, from two independent and impeccable sources, that there had been a battle between the RAF and GCHQ about my original posting notice which had given my appointment at 26SU as 'commanding officer'. As my informant at Marham had told me when that posting notice arrived, RAF Signals Units were usually commanded by Engineering Branch officers. At the time, that had seemed to me not unreasonable since, by and large, aircrew officers didn't know very much about signals engineering. However, for a few weeks that posting notice was correct.

My posting to the Russian Course in 1976 and onwards to 26SU had come at a time when the mandarins at GCHQ were quite independently, and for their own 'intelligence' reasons, trying to bring the RAF signals units under the command of GD officers rather than engineers. Perhaps I had been selected because I was available, had volunteered to learn Russian, and had already served one operational intelligence appointment in Singapore in 1965/6 during the Confrontation between Malaysia and Indonesia. The upper echelons of the RAF Engineering Branch had no wish to lose any command appointments to the GD branch so GCHQ lost that little battle and the RAF Engineering Branch won. My posting notice had been amended accordingly.

A disturbing incident on the way back to Gatow from Teufelsberg

Berliner Funkturm , the Berlin Radio Tower dates back to the mid-1920s but is no longer used as a radio transmitter..

One day my wing commander Boss, who was an engineer, was suddenly taken ill while at work in his office at Teufelsberg and had to be admitted to the Berlin Military Hospital (BMH) just off the Heerstrasse and close to the Olympic Stadium. Before he was driven off to hospital he handed over his safe keys to me, briefed me on some ongoing operations (military ones not medical ones) and reminded me to ensure that the change of command was officially promulgated. At the end of work that day I experienced one of the pleasures of being the acting Boss because, for the very first time, I was able to drive his large and very powerful Opel staff car. 26SU had inherited that unique car from BRIXMIS and it had an armour-plated under-surface. Because of who had used it in the recent past, as well as who currently used it, that particular Opel was well-known to all the international security and intelligence services in the city on both sides of The Berlin Wall.

The Opel was an automatic but because of its weight and length it was cumbersome to drive and so, having seen my Boss safely off in the ambulance to BMH, I drove it from Teufelsberg to Gatow quite slowly, getting used to the handling. I had no passengers. The 30 minute trip was uneventful - or so I thought. I parked the Opel in the slot at the front of the Officers' Mess designated for OC 26 Signals Unit and went inside. I was met in the foyer by the squadron leader RAF policeman who was in charge of the RAF Provost and Security Services in Berlin.

"Hello Tony," the P & SS man said, in what I thought was a rather cool manner. "May we go to your suite, please? By the way, did you leave the keys for the Opel in the car?"

I answered yes to both questions. Service cars were routinely collected each evening from outside Messes and Married Quarters and taken off to the MT section by duty drivers. We sat down in my private lounge along the corridor from the foyer. It was not unusual for me to be visited by RAF policemen because, apart from routine police business, they also dealt with all security matters - and there always seemed to be lots of those in Berlin. I assumed he wanted to tell me about something or someone connected with my work - and I was right! Through the window I could see several RAF policemen inspecting the Opel closely, front, rear and underneath. Now that was unusual. The security man took his notebook out and I knew then that this was not a social visit: it was official - and it was personal.

"Did anything unusual happen on the drive from Teufelsberg to Gatow?" he asked. It was the sort of vague, introductory question frequently used by policemen in the hope that their victim might confess to something.

"Not that I can recall," I answered, going immediately on the defensive. "I can assure you I didn't exceed the speed limit. It was the very first time I've driven the Opel and I was getting used to it."

As I mentioned earlier, for a British serviceman to exceed the strict 50 kph speed limits in the city was a serious matter.

"When you were driving along the Teufelssee Chaussee did you notice anything unusual? Did you, for instance, see anything in your rear view mirror?"

"Not that I can recall," I replied truthfully. The Teufelssee Chaussee was the secluded road through the Grunewald between Teufelsberg and the Heerstrasse.

"At 1727," continued the P & SS man consulting his notes, "a jogger reported that you passed him on the first bend. The jogger was resting on a bench set well back from the road so you probably would not have noticed him. A woman and a man rushed out from the trees just after you had passed them. The woman quickly laid herself down on the road and the man then took a photograph of the woman lying, apparently dead or injured, in the road. The jogger was certain that the picture would include the rear of the 26SU Opel - a well-known car in Berlin as you know. The man and woman then disappeared back into the trees and the jogger, wisely, quietly went off in the other direction and reported what he had seen."

"What are you implying?" I asked.

"That you were being set up for failing to stop after a serious accident. Fortunately, the jogger was not seen, either by the man or the woman; they were too engrossed in what they were doing. Luckily for you, Tony, that jogger works for us - so I know it was a set up. That's how I was able to get here so quickly and ask you these questions. You should consider yourself very fortunate."

"What are you going to do now?" I asked, beginning to realise that being the Second in Command of 26 SU might have some drawbacks.

"Nothing! We wait to see if the Soviets, or the East Germans, try to make use of their photograph either to blackmail you or to embarrass the Allies. In the meantime, please always keep in mind that this city is a hotbed of spies. You need eyes in the back of your head - and whenever you're driving in Berlin, in any vehicle, you should certainly scan your rear view mirror to see what's going on behind you."

I was suitably chastened as well as worried. Had I been the target? Had my Boss been the target? Had the car been the target? I never did find out, but it was not by any means the last odd thing to happen to me in Berlin.

A Soviet cocktail party - males only

Any interpreter (or spy!) will tell you that it is quite difficult to pretend convincingly that you don't understand a foreign language when you are unexpectedly spoken to in that language. A card popped up in my In Tray one day inviting me, by name and appointment, to attend a cocktail party being held to mark the end of the Soviet Air Force's spell in command of the Berlin Air Safety Centre (BASC). I pleaded that it would look impolite if I didn't accept the invitation to attend this function to which all the Commanders and Second in Commands from all the disparate units based in both West and East Berlin had been invited. HQ RAF Germany's reluctance to allow me to go suggested that none of my predecessors had been invited to previous functions at BASC but eventually I was given permission to attend, but with two provisos: I was not to let on that I could speak Russian and I was to be accompanied at all times by a Russian-speaking RAF air traffic controller serving at BASC. The officer selected for that onerous job had been on the Russian Language course at RAF North Luffenham with me.

All British, French and American guests were individually hosted at the Cocktail Party by a Soviet officer. Nothing sinister in that, just common politeness. Because it was a social occasion, everyone wore lounge suits rather than uniform. I was hosted by a chap called Yuri who spoke excellent English in the so-called 'North Atlantic' accent that was taught in Soviet language academies of the time. I have no idea what Yuri's job was and protocol required that no-one asked that question of anyone else. However, my RAF host whispered to me that he had never seen Yuri at BASC before. We drew our own conclusions!

It was actually a rather pleasant occasion with duty free booze flowing like water and everyone jabbering away as they tend to do at cocktail parties. Folk were trying to score points off each other but without talking about their jobs or families and without divulging any national secrets. During the two-hour long party, Yuri stuck close to my side and introduced me to quite a few Russians by name but without mentioning their jobs or military ranks - or mine. Either Yuri or my RAF host politely, but largely unnecessarily, translated everything into English for me - and translated into Russian everything I said in English.

The standard opening gambit seemed to be whether we had ever been to each other's country. No-one I asked had ever been to England, and of course I had never been to Russia but we usually agreed that it would be nice to have the opportunity if and when "the situation improved." I remember having a very brief conversation with someone who asked my opinion on the merits of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and its permanent conductor Herbert von Karajan. I replied that I was a great fan of both, which was true. In return I asked his opinions of Dmitri Shostakovich's symphonies - but Yuri terminated that exchange without translating my question. Yuri, presumably, didn't know whether Dmitri Shostakovich was still persona non grata in the Kremlin. Neither did I!

I did wonder, though, why the subject of classical music should have been brought up. Had someone briefed Yuri that one of my early ambitions had been to become a professional musician? Was he showing off to me or was he following orders? In fact we had always been told throughout my time in the RAF V Force from 1960 to 1976 that the Soviets kept a personal file on all RAF aircrew and assiduously collected and filed whatever personal data they could obtain about RAF V Force aircrew by monitoring national and local newspapers and magazines and any other unclassified sources they came across. (How much easier it must be for our potential enemies in these days of Twitter, Facebook and personal websites!)

The cocktail party was quite fun really - certainly more fun than the average cocktail party, in spite of the total lack of ladies. I remember thinking, "So, no honey traps tonight then."

As the evening drew towards its conclusion, all the guests started to line up with their Soviet hosts to bid a formal farewell to the departing Soviet Commander. I heard the American guest in front of me say, haltingly, "Good night Comrade General" in a tortured Russian accent. The American should have been briefed that the Russian word for 'comrade', tovarishch, should only ever be used between citizens of the Soviet Union. The General, ignored the minor gaff and politely smiled an acknowledgement.

Then it was my turn. I suddenly realised that I'd become separated from my RAF host but Yuri was still at my elbow doing his duty. He stepped forward and announced me, in Russian, as "Major Cunnane from number 26 Signals Unit at RAF Gatow". So much for my cover! Trying to give the impression that I didn't understand Russian, I shook hands with the General while I mimicked the American who had been in front of me by saying, "Good night Comrade General" in a deliberately poor Russian accent. The general, with what seemed to me to be a sympathetic smile, responded in perfect English - and using my correct rank: "Come now, Squadron Leader Cunnane, we all know you speak excellent Russian. I am very pleased you were able to get permission to come to my farewell party."

Any further comment by me, in English or Russian, seemed superfluous. Yuri led me to the exit where he smiled and said in Russian as we shook hands, "Better luck next time, Tony!"

My RAF host was waiting anxiously for me at the exit and had overheard Yuri's final remark. "What did Yuri mean by that?" he asked.

"I don't know!" I lied, shrugging my shoulders.

One of my jobs was to escort visiting VIPs who were unfamiliar with Bertin

This is the Glienicke Bridge across the Havel River connecting West and East Berlin. It was often used to exchange spies from one jurisdiction to the other.

One of my regular 'additional tasks' was escorting visiting British VIPs - and there were many of them because West Berlin was a popular place to visit. Such visits were known as protocol visits: the VIPs were invariably officially sponsored because the Government was very keen that senior officials should see for themselves how West Berlin operated. Most of the VIPs I hosted were from either GCHQ or MoD. Some came on working visits because they were employed in departments that had responsibilities for, or an official interest in, what 26 SU did. One or two visitors I escorted did not tell me why they were in Berlin.

I always tailored my visits according to the wishes of the visitors and the time available but certain locations I always included: the famous, or infamous depending on your viewpoint, Checkpoint Charlie where the US Sector met East Berlin in the centre of the city and the Reichstag, the former seat of the Berlin Government, only a stone's throw from the Brandenburg Gate. When time permitted I included a drive to the northern limit of the French Sector because in the late 1970s that was the most picturesque and unspoilt part of West Berlin. Depending on the time available, I used to include the 'preserved' ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche, the magnificent church all but destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1943, and the superb shopping areas along the Kurfürstendamm, both in the British Sector. (That was the area where the devastating terrorist attack of 19 December 2016 took place during the Christmas Market.)

There was a policy during my time that military visitors and their escort should wear uniform on protocol tours by day and appropriate civilian dress for evening events. When a VIP tour included an evening visit to a restaurant, the escort was required to let the restaurant know in advance the status of the visitor (the number of ranking stars he had) so that the Maître D' could ensure that appropriate compliments were paid on arrival and throughout the meal. I quickly learned that Le pavillon du lac, beautifully located in the Tegel district at the northern end of the French Sector, was by far the best place in Berlin to dine elegantly when you wanted to impress VIPs. Fortunately I was authorised to sign the bill for both the VIP and me and the restaurant presumably sent it off somewhere for payment.

Except on evening functions I almost always did the driving myself in an RAF Staff Car so that, if it was appropriate, we could have classified conversations as I pointed out various places of military as well as civilian interest. Certain VIPs were allowed to cross the Wall for an official tour of East Berlin, something denied to me and most servicemen at 26 SU. When I asked why the VIPs could go on a conducted tour of the East and I could not, I was informed that there was a mutual agreement between the four Allied Powers that star-ranking visitors would not be interfered with when visiting each other's sectors of Berlin. It was such a gentlemanly cold war!

One day I was asked to do one of my West Berlin tours for a visiting air vice-marshal (2-star). I checked his security level and special clearances before I met him. It was necessary to do that with all visitors, however high their rank or status, to avoid inadvertently giving classified information to those not entitled, and to avoid patronising those whose clearances were higher than mine. The air vice-marshal told me to remove the two-star plates, to which he was entitled, from the front and back of the car because he didn't want to attract undue attention to himself. I refrained from pointing out that the Soviets and East Germans almost certainly already knew who he was, where he was from, and why he was in Berlin - which was more than I knew.

Towards the end of the tour the air vice-marshal asked to be taken to Marienfelde, at the southernmost end of the American Sector, to take a look at a USAF facility close to the DDR border. I stopped the car, keeping the engine running, at a slightly elevated spot I had used several times before, and pointed out things of particular interest to my guest. Although I occasionally visited the USAF base at Marienfelde as part of my normal duties, I couldn't take a senior officer into the station without having arranged a visit with the Americans well in advance. There was no reason to conceal ourselves because we were doing nothing illegal but, after chatting for a few minutes, I drew my guest's attention to the watch-tower barely a couple of hundred metres away on the other side of the East German border. Before I could stop him, the air marshal put his cap on and got out of the car to get a better view and to take some photographs.

I called out to my guest through the open car window that if he looked carefully, but casually, at the East German watch-tower, he would see that there were now at least two guards inside watching him through binoculars. I added that one of the other guards would certainly be taking photographs of us through a telephoto lens because they always did. On hearing that my visitor reached into the car and quickly swapped his RAF cap for mine. The air vice-marshal's cap had a double row of gold braid (aka scrambled egg) denoting his air officer rank; mine was a standard RAF officer cap without any gold braid. "I don't want to be recognised," he said by way of explanation, forgetting that my cap on his head was not consistent with the prominent rank stripes he had on his tunic sleeves. When I pointed that out, he quickly got back into the car and told me to drive off.

Somewhere, Soviet intelligence agents must have mulled over the photographs they had taken showing a squadron leader staff car driver wearing an air officer's cap, and someone in air vice-marshal uniform wearing an ordinary officer's cap. I have often wondered what they made of those photographs - and I wish I had copies!

A night at the Berlin opera with an unusual VIP

Before I enlisted in the RAF in 1953 my life's ambition had been to become a professional musician until I was thwarted for reasons beyond my control. Concerts at the Philharmonie (Philharmonic Hall) by the resident Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, often under the baton of the ageing but still charismatic Maestro Herbert von Karajan, were always sold out within minutes of the Box Office opening. The only way to get a seat was either by joining a very long queue on the day they first went on sale, or by means of a season ticket which were virtually impossible to buy on the open market. Those German citizens who had season tickets invariably had them for life and left them in their wills to other favoured members of their family.

A few so-called Protocol Tickets had originally been allocated to the British, French and American HQs for the use of senior diplomats and they were usually handed on from one incumbent to another. Early in my tour in Berlin I acquired one from a British Army officer, a very fine flautist and a great fan of James Galway who had been the leading flute player with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra between 1969-75. My benefactor had reached the end of his tour and was returning to UK. The season ticket itself was free but that merely reserved a particular seat; I had to pay the full amount (about £75 at the 1979 exchange rate) for each of the many concerts I went to, but it was worth it.

One day in 1980 I was asked to escort a high-ranking civilian, supposedly from GCHQ, to the Berlin Opera House for a performance of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg and I was delighted: I had never been to a live performance of that opera. The Deutsche Oper Berlin was one of two opera houses in Greater Berlin (the other was in East Berlin and so out of bounds to me). I didn't have a season ticket for the Berlin Opera but on this occasion the visitor was sufficiently important for me to be provided with two free tickets which had a face value the equivalent of over £100 each.

The Mastersingers has three very long acts so there was an early curtain-up at 5.30pm and two lengthy intervals during the performance. I met my visitor for the first time when I collected him from his hotel and we then went on by taxi. We were dressed formally in dinner jackets, de rigueur for the Opera House. It was, my visitor told me, his first ever visit to Berlin but that was all I knew about him. He called me Tony once or twice but he was too senior for me to call him anything other than "Sir".

In the first 30-minute interval my guest and I had some refreshments in one of the several bar lounges. In keeping with typical German fashion, we had pre-ordered in advance and the drinks and snacks were waiting on our designated table when we got to it through the crowds. I could tell from our conversation that my guest had no knowledge of opera. That was not unusual in itself; many people went to the Opera not to satisfy their love of the music but just to be seen, or to say they had been. At one point he said to me in a rather louder voice than was wise because the tables were very close together, "It's great fun trying to pick out the spies amongst this lot, isn't it?" I made a sort of non-committal grunt.

At the second interval, 45 minutes long, instead of going to another of the bar lounges my guest suggested we went for a gentle stroll around the Opera House's magnificent corridors and balconies, watching and being watched at what was then West Berlin's most prestigious venue. Eventually, after looking at his watch, my guest murmured that he needed to go to the toilet. Without asking me where they were, he disappeared at high speed towards an area where I knew there were no toilets. About 15 minutes later, when everyone else was already streaming back into the auditorium for the final act of the opera, he returned to where I was waiting, contentedly watching the crowds from a balcony. He looked flustered and muttered, "Sorry about that, I had to meet someone."

During the final act it was obvious to me that my guest was distracted; he kept sneakily looking at his watch and was not concentrating on the action on stage. I got the clear impression that he would have preferred to have given the final act a miss. However, in Berlin during the Cold War one did not ask senior officials what they were there for, where they had been, or to whom they had been talking. It was not done.

It was a virtually silent taxi ride back to his hotel where I dropped him off just before midnight. I had to pay off the taxi driver when I got back to RAF Gatow.

A very worrying night transit through the Berlin road corridor

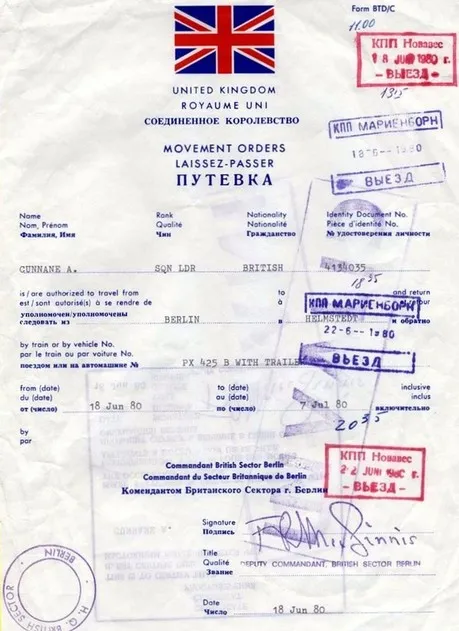

This is one of my 'used' pootyovka

My most worrying incident occurred on the early morning of 26 December 1979. I had remained on duty at Teufelsberg until late evening on Christmas Day trying to make sense of a situation developing thousands of miles away to the east that would soon hit the world headlines. I didn't know it then but the unusual Soviet transport flights into Afghanistan that we were tracking turned out to be the start of the Soviet invasion. After a mere couple of hours sleep, I set out for the long drive back to my home in Lincolnshire to spend what was left of Christmas with my family. I left RAF Gatow at 4am and drove through empty streets to Checkpoint Bravo at the southern end of the American Sector of Berlin.

On arrival at Checkpoint Bravo my documentation was checked by the British Military Police detachment. Although I had already done the trip several times by day, I was given the standard briefing and I signed documents to confirm that I was familiar with the rules and knew what to do in the event of a breakdown or emergency. One of the most important elements of the standard briefing was that there was to be absolutely no interaction whatsoever with East German civilians or military. The reason for that was that the UK, US and French Governments did not recognise the East German state.

A few kilometres further on, after driving through the bleak no-man's land along the totally deserted road, I pulled into the Soviet Checkpoint on the East German border near Dreilinden. The vast floodlit area was empty and it really was very eerie. In accordance with the protocol, I came to a halt alongside a solitary Soviet soldier at the only one of the dozen traffic lanes that was open. I got out of my car, closed the door and locked it. The guard and I then formally saluted each other together, even though I was in civilian clothes. Rank and mode of dress was not important: the salutes were intended to be friendly gestures between Allies. Part of the protocol was that Allied vehicles (that is American, British, French and Soviet) in transit along the military corridors were not allowed to be searched.

I handed my papers to the soldier; he walked slowly around my car, checked that the registration number matched the details on my Pootyovka (Movement Order) and then handed the papers back to me. Not a word was spoken. We exchanged salutes once more and then he indicated that I should walk over to the small building about 200 metres away. Inside that building I pushed my documents through the familiar small hatchway. The window above the hatch was shuttered as usual but by bending down as I slid my papers through, as I always did, I could see that the normally very busy office beyond was almost empty - it was, after all, very early morning on Boxing Day! The person who took my papers was half standing so I couldn't see much of him other than his arms.

A TV was on in the corner of the waiting room, tuned to the main West Berlin channel which was showing a Christmassy music programme. A selection of English, French, German and Russian language magazines and newspapers lay on a table. Conscious of the CCTV camera staring down on me from high up in a corner of the room, I ignored the Russian literature, picked up an English magazine and sat down to wait. Normally, and even at busy times, travel documents came back through the hatch within a very few minutes, warm from the photocopier and authenticated with a Soviet stamp. On this occasion I was kept waiting for 10 minutes and I began to feel uneasy.

When my papers were eventually thrust back through the hatch, I could see that the person doing the pushing was wearing the uniform of a Soviet Army lieutenant colonel rather than the more usual corporal or sergeant. I am quite certain that the officer made sure I could see his rank, one higher than mine, because, quite unnecessarily, he leaned as far forward as the hatchway permitted. He said "Thank you, have a pleasant journey" in excellent English. I returned to my car and showed the documents once again to the guard. He checked that they had been stamped with the Soviet authority to proceed and then handed them back to me. We saluted each other again and I got back into my car.

I made a note of the time and then drove on into the German Democratic Republic. The time was important because I could not afford to arrive at the next Soviet checkpoint, 160 kms away, in less than two hours otherwise I would have exceeded the strict 80kph speed limit somewhere along the route - and that was a crime and contrary to the Allied protocol. Taking too long on the journey would also have raised suspicions because no stops, not even 'comfort' stops, were permitted along the route. Had my car broken down or if, for any other reason, I had to stop inside GDR territory, the protocol required me to remain in my vehicle, place the large Union Jack poster, which was always carried in the glove compartment by British travellers, in the windscreen and wait for British Military Police to arrive. The protocol also forbade us to speak to any German citizen if one should be so foolish as to approach our car (any that did, would very likely be defectors trying to escape to the West).

Those next two hours were a worrying time. It was the first time I had done the journey by night. It was an extremely dark night and there were no road lights! The road was single carriageway for most of the way, with many bends, and often passed through forests and occasionally through small villages which were also in darkness apart from a very occasional street light. I am sure I spent as much time watching my rear view mirror as I did watching the road in front but there was absolutely nothing to be seen and I saw no moving vehicles in either direction. Every few miles I noticed an East German police patrol car parked up in a lay-by with its lights on, or at a road junction seemingly waiting to cross; the crews were doubtless reporting my progress to someone.

It was easy to maintain the 80kph average speed through East Germany; I slowed down for the last 2 or 3 kms as I approached the border area just to make quite sure I would not be early. After 2 hours 5 minutes I pulled up at Soviet Checkpoint Alpha at Marienborn. The procedure was the same as at the Berlin end. After exchanging salutes, I handed my documents over to the Soviet border guard. I noticed that he was older than the average guard but I could see no badges of rank. He waved me over to the Soviet office without even bothering to check my documentation. Now that was very unusual! Inside the hut, my pootyovka was checked and stamped again in a very short space of time and with great relief I went back to my car.

This time, instead of coming out to stand alongside me at the front of my vehicle, the guard remained inside his sentry box, contrary to the protocol. After we had exchanged salutes he held his hand out for my documents. I handed them over at full stretch. Without looking at them, he moved back a further couple of paces into his box and gestured me to move closer. I declined. He spoke to me in colloquial Russian.

"Have you something you wish to swap?" he asked. I believe that British servicemen sometimes handed over bars of chocolate or cigarettes in exchange for a Soviet badge or some other souvenir, as a gesture of Allied friendship, but that was strictly against the rules.

I ignored his question and said in English, "Please check my documents and let me pass." He persisted, always in Russian, for what seemed like ages but was probably only a couple of minutes. I assumed that there were hidden cameras and microphones and that 'they' were trying to get a photograph of me handing over something to the Soviet soldier. In the end I snapped at him and said curtly and loudly in English, "Check my documents and hand them back."

Suddenly a voice came over a loudspeaker inside the sentry box. The language was possibly Ukrainian or some other language similar to Russian: I could understand only a little of what was said but it was certainly an order to the guard. He came smartly out of his box, handed over my documents, still not having looked at them, and said "Thank you squadron leader, Happy Christmas" in English, and saluted. I returned his salute, got into my car in some relief, and drove on.

A few minutes later I was in the safety of the British Checkpoint at Helmstedt. Before leaving my car in the empty parking lot outside the NAAFI (closed for Christmas!), I checked that the black cotton I had stuck between the body of the car and the boot lid before leaving Gatow was unbroken and then went to book in. Travellers were required to report anything unusual that happened during their transit through East Germany and so I had to spend the next hour tediously making a written statement of my little adventure.

When I reached home in Lincolnshire later that same afternoon, the whole world was talking about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan - and I had to pretend to be surprised.

German lessons, play acting and some lip sync for a German film

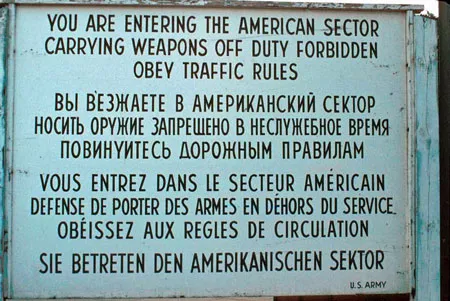

The area around the famous Checkpoint Charlie was very congested

When I had first arrived in Berlin, I started having German lessons from a truly delightful lady called Frau Emmy Lempfuhl. I was introduced to Frau Lempfuhl by a diplomat friend in the British Military Government (BMG), a strange organisation that had its HQ in what had been Berlin's 1936 Olympic Stadium. He told me that Frau Lempfuhl gave German lessons to many British servicemen from the highest rank down to the lowest and I was assured that she had been vetted by the security people.

Like countless young German girls in 1945, Emmy had suffered great indignities at the hands of the Soviet troops as they swept unbridled into Berlin in the final days of the war (my briefers told me that, not Emmy herself). I found to my delight that Emmy taught the language my way - the old-fashioned way! She believed that it was essential to learn grammar as well as vocabulary and I progressed rapidly with her one-to-one instruction. At her suggestion, we agreed to use first names during lessons but I continued to greet her as Frau Lempfuhl when I first arrived for a lesson and only reverted to Emmy two or three months later. It seemed more polite to me and, in any case, it helped me to get to grips with the two forms of the second person singular.

Emmy knew that I was a Russian linguist and she knew where I worked, although I never mentioned either to her. I always suspected that she knew far more about my job than she ever let on but we never discussed 'shop' and I never mentioned Russia or spoke Russian in her presence. After about six months of having my weekly private lessons in Brooke Wavell Barracks in Spandau, where Emmy held her regular formal classes for British soldiers newly arrived in Berlin, she invited me to continue the lessons in her flat where she lived with her sister. As a matter of routine I reported that to the security people and, thereafter, most of my lessons were held in her flat. I cannot now remember exactly where the flat was but it was on the 2nd or 3rd floor of one of the typical enormous, pre-war Berlin town houses. Emmy's sister shared the flat with her but I met her only once; she didn't speak any English - not in my presence anyway.

After a year my spoken German was good but obviously still not perfect. When I went into Reception at a Hotel way down south in beautiful Garmisch-Partenkirchen and expressed my requirements in German, the lady receptionist replied in English. However, someone (an Englishman) told me later that Bavarians are very jealous of their particular version of German and enjoy correcting tourists who use 'standard German'.

One day I told Emmy in general conversation that I had somewhat reluctantly been appointed Officer in Charge of the RAF Gatow Theatre Club and that I had subsequently been persuaded to 'tread the boards' for the very first time since appearing as Prince Charming in my primary school production of Cinderella in 1943 when I was eight years old. At the time I took over as Officer i/c, the club members had already decided that their next production would be The Diary of Anne Frank. It turned out that the Producer was short of a 'mature' man to play the minor part of Dr Dussel the dentist and the Producer persuaded me to step in. Imagine the fuss created in high places by choosing to put on that particular play in Berlin. A staff officer, who happened to be visiting Berlin from HQ RAF Germany in Rheindahlen, asked me the loaded question: "Are you sure it's appropriate to put on The Diary of Anne Frank in Berlin?" I considered my career prospects and then decided to back the club members. I think that was probably not the answer expected of me but the production went ahead and played to full and appreciative houses.

Intoxicated by the thrill of acting (!!) I then took part in four more Theatre Club productions: Wolf's Clothing by Kenneth Horne (I played Brian Rix's part); The Anniversary by Bill McIlwraith; and Unexpected Guest by Agatha Christie. My final appearance, far less controversial, was playing Toad in what was said to be the German premiere of Toad of Toad Hall by Kenneth Grahame. I was only vaguely familiar with the story and I was dismayed when I realised the vast number of lines I would have to learn. I recorded myself reading the entire play onto my Revox reel-to-reel tape recorder, leaving gaps just long enough for me to deliver Toad's lines when I replayed the tape - which I did many dozens of times until I was word perfect. Not once on any of the six performances (each to a full house) did I need the services of the Prompter. I was not the world's most accomplished actor but I was quite proud of that feat of memory. Sadly there are no photographs of my performances!!

In the last few weeks of my tour in Berlin, immediately after the final performance of Toad, I was invited to take on a small part-time job doing the English 'voice-overs' for a German film that was being prepared for English-speaking release. Someone (Emmy perhaps?) had recommended me to the Producer; she gave me an audition and immediately decided that my voice, accent and intonation was just what she wanted.

This was the warning sign at Checkpoint Charlie but there was no way anyone could pass through accidentally!

The film was a lengthy and, it has to be said, very boring documentary about German cars which was being prepared for its UK release. The film studio was very close to the Berlin Wall, literally just around the corner from Checkpoint Charlie, and the company was the very one that had dubbed the film My Fair Lady into German. For that they had used a girl with the very distinctive Berlin accent to play Eliza Doolittle, the Cockney girl (Audrey Hepburn in the original).

Most of my task was quite straightforward: all I had to do was read aloud the words from the script as the film was playing silently on a large screen. That part of the job didn't take very long - just a couple of days I seem to recall. Occasionally I was able to suggest small changes to make the English script sound more natural. The many lip-sync scenes, however, were much more demanding; it was a difficult art that I had to learn from scratch. Fortunately, someone had very skilfully translated the German script into English so all I had to do was synchronise my speech with the lips of the German actor on the screen!

Filming those lip-sync sequences turned out to be frustrating and time consuming; they took place over several days and required great patience on the part of everyone in the studio. I sat on a high stool watching a large screen as the film was played, silently of course, a few seconds at a time. Standing by my shoulder was the lady who had written the English words. I found it was impossible to look at the actor's lips on the screen and read my words from the script at the same time because I was always late starting. So I had to memorise my scripts and try again. I began to despair of ever getting it right and I could detect tension building up amongst the various technicians. My mentor told me that I was trying too hard - a common mistake apparently. It seems I was concentrating too much on the lips of the German speaker on the film and as a result my speech came out haltingly and in a monotone. We tried another method. A red warning light at the side of the screen flashed three times: I was told to breathe in on the first two flashes and start speaking instantly on the third. All of a sudden like falling off the proverbial log, I got the hang of it. We then progressed rapidly and the studio tension suddenly vanished!

The job was completed just a few days before I left Berlin for the final time at the end of my tour. At the run through of the complete film, it was quite fascinating to watch the lip-synced scenes where my voice came out over the German actor's face; it really did look as though he was talking and to my surprise, my voice, still with its slight northern English accent, seemed entirely natural. The entire production team laid on a small, surprise party for me. The Producer told me that I had learned the job faster than many semi-professionals they had to deal with. However, it turned out to be rewarding in the other sense of the word. As I was leaving the studio for the final time, I was handed a surprisingly large fee in cash - and I had thought I was doing it free for the love of the art and Anglo-German relations. Sadly, I never did see the results of my efforts in an English cinema.

Dinner with a German spy and his frau

During most of my 30 months at No 26 Signals Unit, one of my secondary administrative duties on the main base at RAF Gatow had required me to deal on an almost daily basis with one particular German civilian. To protect his identity, for reasons which will become clear, I will refer to him as Herr Franks. He never asked me about my work at 26SU and I never asked him about his earlier life. To get on well with Germans of a certain age (roughly my age!), it was neither wise nor polite to ask them what they or their fathers had done during the war.

Just before I was due to leave Berlin, Herr Franks invited me to a farewell dinner with him and his wife and I was delighted to accept. I was entitled to an RAF car and driver so I didn't have to worry about drink-driving. When I arrived at Herr Frank's home bearing a bouquet of flowers for Frau Franks (with an odd number of stems as German social protocol requires), I was rather surprised to find that there would be just the three of us at dinner. They lived in a beautiful house only a few miles from Gatow and as I entered a fabulous smell of food greeted me. When we sat down to dinner it turned out that the smell emanated from the main course, a concoction of snails in a thick, savoury sauce. I have an allergy to shellfish but, although I had never sampled snails and they are not shellfish, they do live in shells and the very thought of eating them made me apprehensive.

"Do you like snails," asked Frau Franks as she brought the steaming, fragrant dish to the table. We conversed in a mixture of German and English.

"I've never had any," I replied truthfully, but added untruthfully, "I've always wanted to try some."

Herr Franks ladled a large helping of the food onto my plate and he and his wife bade me start. I looked carefully at the suspicious objects floating in the sauce and then bravely dug in. I tentatively chewed into one of the snails and found it rubbery and unyielding. I couldn't taste anything unpleasant because the excellent garlic sauce disguised any flavour the snails might have had. Without realising it, I ate speedily, swallowing the snails whole, with the misguided idea that the sooner I got it over with, the better. I soon emptied my plate - long before my hosts had emptied theirs. I sat back contentedly in my chair sipping a truly excellent Liebfraumilch Auslese.

"You seem to have enjoyed your first snails," beamed Frau Franks and, as I nodded enthusiastically while dabbing my lips with a napkin, Herr Franks spooned another large helping onto my plate. "There's plenty more," he added.

I began to feel rather unwell before the long meal was finished but I managed to conceal that and tried to concentrate on the conversation. Herr Franks asked how I was getting home from Berlin and whether I was looking forward to my next job.

"I'll be driving home through the Central Corridor and then right across France before taking the ferry from Calais to Dover," I answered. "I don't know what my next job will be - I expect they'll tell me before my disembarkation leave is over."

That was another lie. I knew perfectly well that I was posted as an instructor to the Joint Service School of Intelligence at Templar Barracks, Ashford in Kent. I had pre-booked a room in the Officers' Mess at Templar Barracks to recover from the drive and to drop off some of my belongings. That was why I intended using the short sea crossing from Calais to Dover rather than one of my preferred, but much longer, routes in a cabin on the overnight car ferry from either Hamburg or Bremerhaven to Felixstowe.

"I believe I heard someone saying you were being posted to an Army unit in Kent," said Herr Franks, his bushy eyebrows raised questioningly.

"I don't know where they got that from," I lied for the third time and changed the subject.

I started to feel better. Over brandy, liqueurs, Schwartzwälde-kirschtorte with added fresh cream, and with scrumptious Bavarian chocolates and coffee to follow all that, the conversation turned to music. Frau Franks put an LP of Wagner's Siegfried Idyll on the hi-fi in the corner of the room. As it happens, it was a recording of von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic that I often played on my own equipment in my suite in the Officers' Mess at Gatow. As we listened to the dreamy work, which was Wagner's 1869 birthday present to his second wife, Cosima, I explained how much I had enjoyed my frequent visits to the Berlin Philharmonic Hall and the West Berlin Opera House.

"Siegfried Idyll is one of my favourites," I said, "I have an LP of this particular version in my suite in the Mess."

"Yes I know," said Herr Franks. Alarm bells sounded in my head. How did he know? Perhaps he was just showing off? Surely he was not trying to recruit me?

When the music slowed to a close, fading very gradually into silence (Wagner had written bedeutend langsamer in the score), I sensed that it would be an appropriate time to say my farewells. On the spur of the moment, I offered to hand on to Herr Franks my Philharmonie protocol season ticket. He was overcome with gratitude at my offer and, of course, accepted it. It was my way of thanking my hosts for an excellent evening - and eased my conscience for having lied to them three times. Neither Frau nor Herr Franks seemed disappointed that the season ticket was for a single seat, not a pair.

There are a couple of corollaries to that story.

When I unpacked my crates on arrival at my new unit in Kent, my LP of Siegfried Idyll was missing. About 10 years later, shortly after the Wall had been demolished and Germany reunited, I read on the Internet that the very same 'Herr Franks' had been sent to prison, having been convicted in a German court of being a long-standing spy for East Germany. His duplicitous activities, which had started before my time in Berlin and continued afterwards, had apparently been known about for a long time. I also read that many Germans had worked as spies for both East and West at the same time and that this was well known by the agencies of both sides. Herr Franks, it seems, came into that category. But who was he working for when he invited me round for the farewell dinner?

I had an email in about 2005 from someone who claimed to be very interested in writing a book about the years of the divided Germany. He had read a version of this story then on my website and wanted to know the real name of Herr Franks so that he could go and interview him for his book. I refused several times in a series of emails and told him that if he really was a historian, he would know how to find out what he needed to know from official sources - or by searching on the Internet as I had done. Eventually he stopped sending me emails.

I do wonder who got my season ticket to the Philharmonie. Before the Philharmonie was refurbished a few years back, I often caught sight of what was once my seat during the many TV concerts relayed via Sky Arts channels. I froze the frame when I could, to take a closer look at the man sitting in what used to be my seat. I hoped it would be Herr Franks, but it never was.

All text and images on this website are copyright Tony Cunnane 2017 except where otherwise indicated.

You can download a copy of Tony's book here in 3 formats: pdf, mobi or epub